BCG

BCG, or bacilli Calmette-Guerin, is a vaccine for tuberculosis (TB) disease. This vaccine is one of the first vaccines to be administered after birth or ideally before hospital discharge.

• A single dose of BCG vaccine is required to provide lifetime immunity.

• Booster doses of BCG vaccine are not recommended by WHO.

• BCG is preferably given at birth to provide protection in the early years when infection can often lead to diseases such as miliary tuberculosis or tubercular meningitis.

• Infants may receive the vaccine soon after birth or later, but preferably before exposure to persons with active tuberculosis.

Human TB has existed for thousands of years. No country is TB-free, and the disease is endemic in most poor countries of the world. It is estimated that about one-third of the current global population is infected asymptomatically withMycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), of whom 5-10% will develop clinical disease during their lifetime.

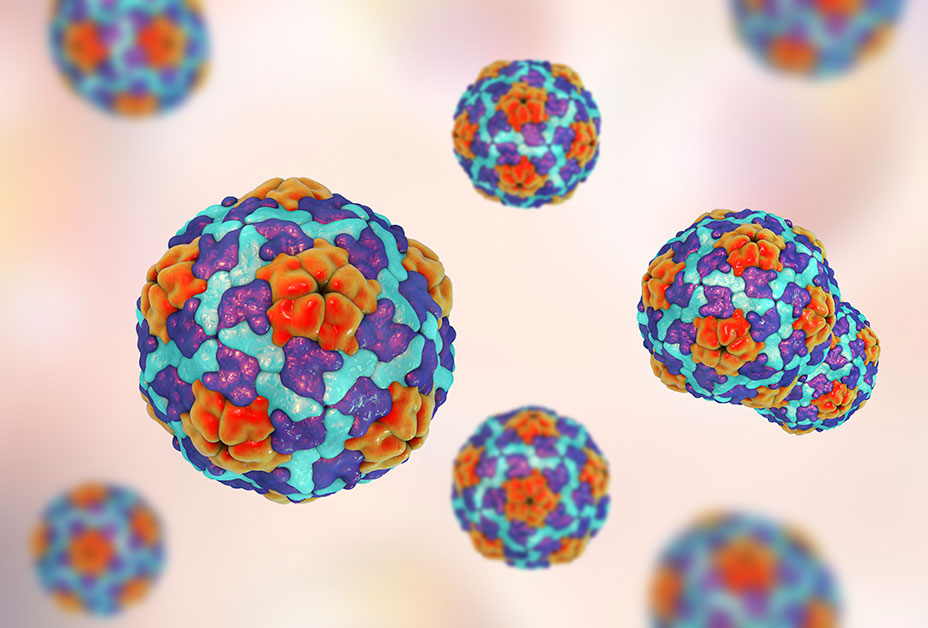

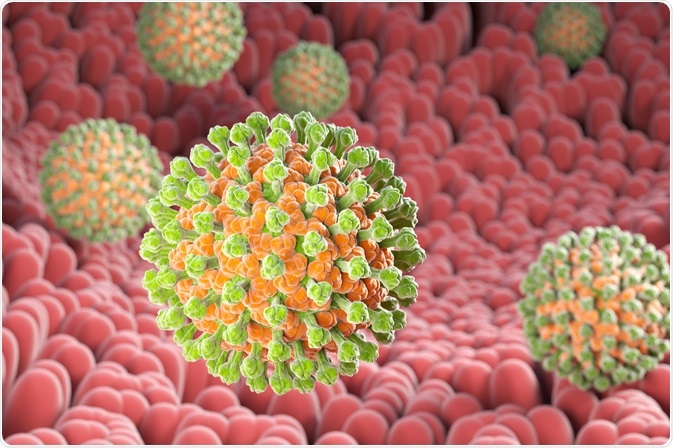

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) is the name of a group of viruses that includes more than 100 different types. More than 30 of these viruses are sexually transmitted, and they can infect the genital area of men and women including the skin of the penis, vulva, or anus, and the lining of the vagina, cervix, or rectum. Some of these viruses are called "high-risk" types; they may cause abnormal Pap tests and can also lead to cancer of the Cervix, vulva, vagina, anus, or penis. Others are called "low-risk" types; they may cause mild Pap test abnormalities or genital warts.

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

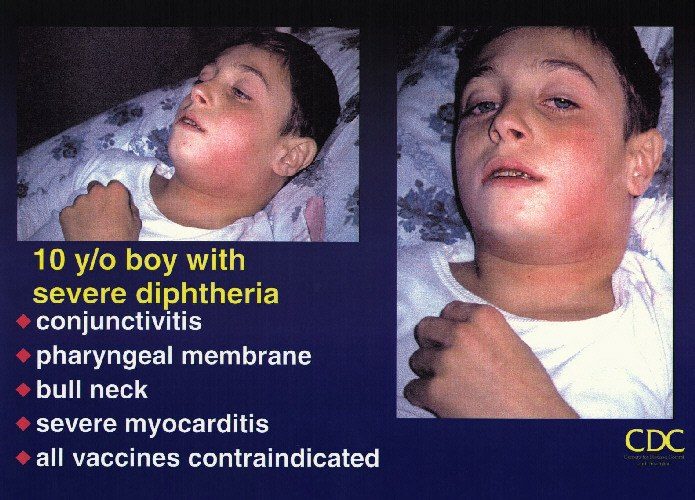

Diphtheria

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

• DTaP: Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine; given to infants and children ages 6 weeks through 6 years. In addition, four childhood combination vaccines include DTaP as a component.

• DTwP: Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and whole cell pertussis vaccine; given to infants and children ages 6 weeks through 6 years. In addition, four childhood combination vaccines include DTwP as a component.

• Tdap: Tetanus and diphtheria toxoids with acellular pertussis vaccine; given to adolescents and adults. Pregnant women should receive Tdap during each pregnancy.

Hepatitis A

.bmp)

HAV is spread from person to person by putting something in the mouth that has been contaminated with the stool of a person with HAV infection. This type of spread is called "fecal-oral." This can happen in a variety of ways, such as when an infected person who prepares or handles food doesn't wash his or her hands adequately after using the toilet and then touches other people's food. A person can also be infected by drinking water contaminated with HAV or drinking beverages chilled with contaminated ice. Contaminated food, water, and ice can be significant sources of infection for travelers to many areas of the world. For this reason, the virus is more easily spread in areas where there are poor sanitary conditions or where good personal hygiene is not observed. Most infections in India result from contact with a household member or a sex partner who has hepatitis A; however the proportion of cases of hepatitis A among international travelers, illegal drug users, and men who have sex with men has been increasing. Casual contact, as in the usual office, factory, or school setting, does not spread the virus.

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

• HAV is spread by getting HAV-infected fecal matter into a person’s mouth who has never had hepatitis A (e.g., an HAV-infected person who doesn’t wash his or her hands after using the bathroom and then handles food for public consumption or an infected person who has sex with a person who has never had hepatitis A). HBV and HCV are spread when an infected person's blood or blood contaminated body fluids enter another person's bloodstream.

• HBV and HCV infections can cause lifelong (chronic) liver problems. HAV does not.

• There are vaccines that will protect people from HAV infection and HBV infection. Currently, there is no vaccine to protect people from HCV infection.

• There are medications that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of chronic HBV and HCV infections. • If a person has had one type of viral hepatitis in the past, it is still possible to get the other types.

Hepatitis B

The spread of HBV occurs when blood from an HBV-infected person enters the body of a person who is not infected. This can occur through having sex with an HBV-infected person without using a condom (the efficacy of latex condoms in preventing infection with HBV is unknown, but their proper use may reduce spread of HBV). HBV is also easily spread by sharing drugs, needles, or "works" when "shooting" drugs. The risk of HBV infection from HBV-contaminated needle sticks is much greater than the risk of spreading HIV by this method. Other types of percutaneous (through the skin) exposures, including tattooing and body piercing, have also been reported to result in the spread of HBV when good infection control practices have not been used. Unsafe injections

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

HBV is also easily spread by sharing drugs, needles, or "works" when "shooting" drugs. The risk of HBV infection from HBV-contaminated needle sticks is much greater than the risk of spreading HIV by this method. Other types of percutaneous (through the skin) exposures, including tattooing and body piercing, have also been reported to result in the spread of HBV when good infection control practices have not been used. Unsafe injections in medical settings are a major source of HBV spread in many developing countries.

HBV is also spread through needle sticks or sharps exposures on the job and from an infected mother to her baby during birth. Breastfeeding has not been associated with the spread of HBV.

HBV can also be spread during childhood. Most early childhood spread occurs in households of people with chronic (life-long) HBV infection, but the spread of HBV has also been seen in daycare centers and schools. The most likely way that the spread of HBV occurs during early childhood involves contact between an infected person's body fluids (e.g., their blood or drainage from their wounds or skin lesions) and breaks in the child's skin. HBV can be spread also when an HBV-infected person bites another person who is not infected. HBV can be spread also by an infected person pre-chewing food for babies, and through contact with HBV from sharing personal-care items, such as razors or toothbrushes. The virus remains infectious and capable of spreading infection for at least seven days outside the body. Virus can be found on objects, even in the absence of visible blood. HBV is not spread through food or water, sharing eating utensils, hugging, kissing, coughing, and sneezing or by casual contact, such as in an office or factory setting. People with chronic HBV infection should not be excluded from work, school, play, childcare, or other settings.

• Discard used items such as bandages and menstrual pads carefully so no one is accidentally exposed to your blood.

• Wash hands well after touching your blood or infectious body fluids.

• Clean up blood spills; then clean the area again with a bleach solution (one part household chlorine bleach to 10 parts of water).

• Tell your sex partner(s) you have Hepatitis B so they can be tested and vaccinated (if not already infected or vaccinated). Partners should have their blood tested 1-2 months after three doses of vaccine are completed to be sure the vaccine worked.

• Use condoms (rubbers) during sex unless your sex partner has had hepatitis B or has been immunized and has had a blood test (as described above) demonstrating immunity to HBV infection. (Condoms might also protect you from other sexually transmitted diseases).

• Tell household members to see their doctors for testing and vaccination for hepatitis B.

• Tell your doctors that you are chronically infected with HBV.

• See your doctor every 6-12 months to check your liver for abnormalities, including cancer. • If you are pregnant, tell your doctor that you have HBV infection. It is critical that your baby is started on HBIg and hepatitis B shots within a few hours of birth.

DON'Ts • Don’t share chewing gum, toothbrushes, razors, washcloths, needles for ear or body piercing, or anything that might have come in contact with your blood or infectious body fluids.

• Don’t pre-chew food for babies.

• Don’t share syringes and needles. • Don’t donate blood, plasma, body organs, tissue, or sperm.

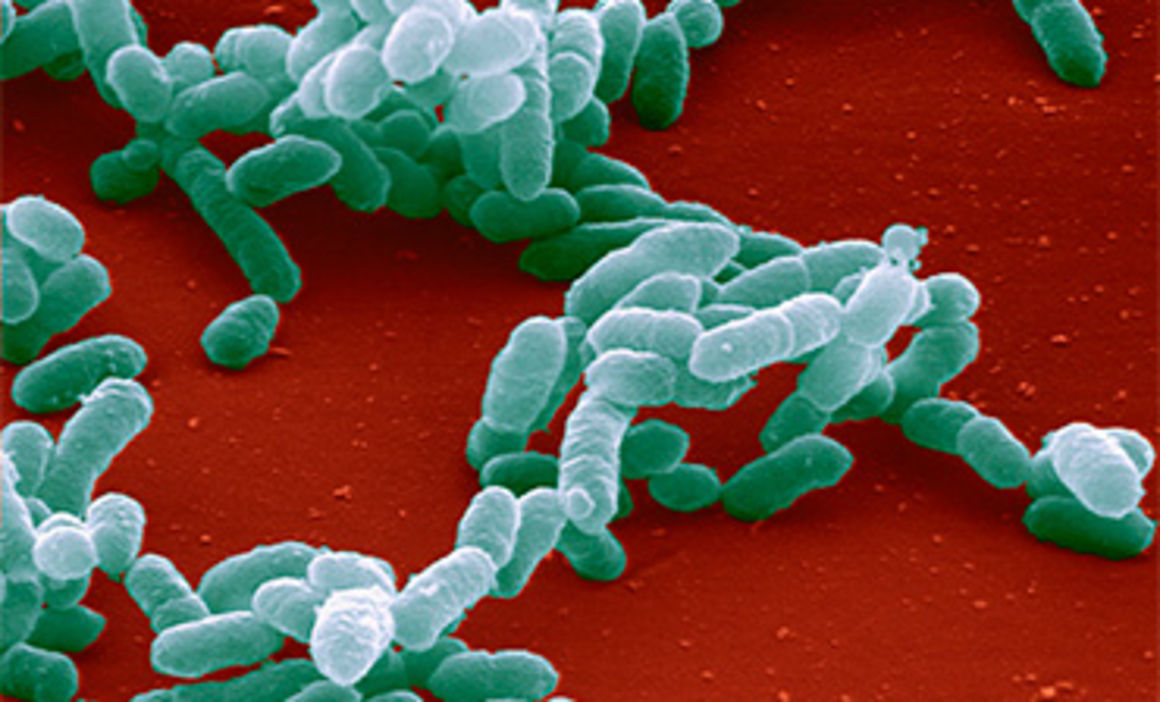

HIB

Hib disease is caused by a bacterium, Haemophilus influenzae. There are six different types of these bacteria (a through f). Type b organisms account for 95% of all strains that cause invasive disease, and this is the type against which the Hib vaccine protects.

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Influenza

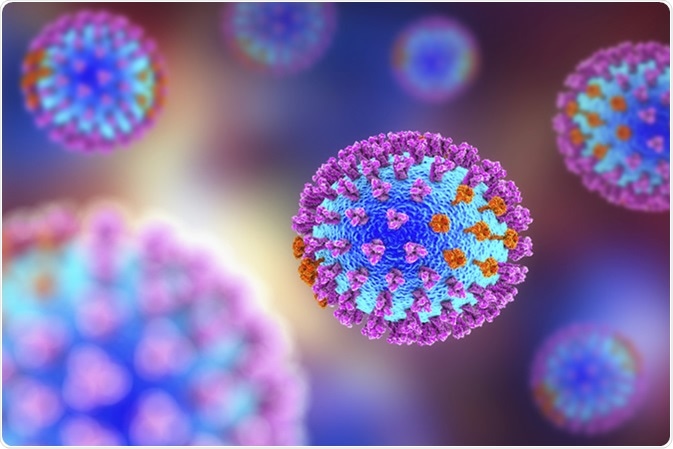

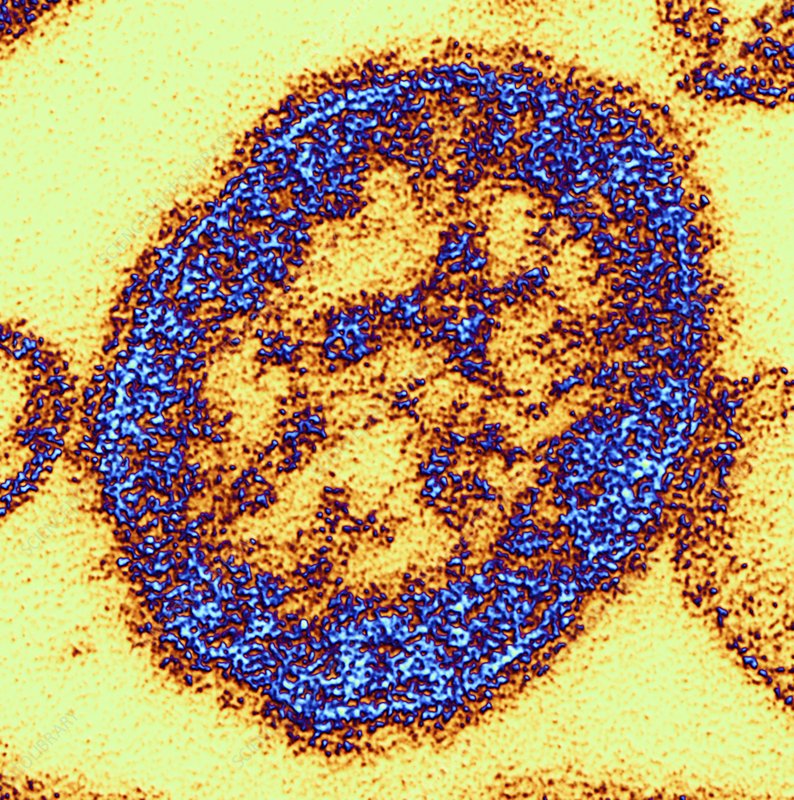

Viruses cause Influenza. There are two basic types, A and B. Their genetic material differentiates them. Influenza A can cause moderate to severe illness in all age groups and infects humans and other animals. Influenza B causes milder disease and affects only humans, primarily children. Subtypes of the type A Influenza virus are identified by two antigens (proteins involved in the immune reaction) on the surface of the virus. These antigens can change, or mutate, over time. When a "shift" (major change) or a "drift" (minor change) occurs, a new Influenza virus is born and an epidemic is likely among the unprotected population.

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Influenza viruses cause disease among persons of all ages. Rates of infection are highest among children, but the risks for complications, hospitalizations, and deaths from Influenza are higher among persons age 65 years or older, young children, and persons of any age who have medical conditions that place them at increased risk for complications from Influenza. Case reports and several epidemiologic studies also indicate that pregnancy can increase the risk for serious medical complications of Influenza.

In nursing homes, up to 60% of residents may be infected, with up to a 30% fatality rate in the infected. Risk for Influenza-associated death is highest among the oldest elderly persons age 85 years and older are 16 times more likely to die from an Influenza-associated illness than persons aged 65-69 years.

Children age two years and younger have hospitalization rates second only to people age 65 years and older. Children younger than age one year are the most likely to be hospitalized. Influenza-associated deaths are uncommon among children but represent a substantial proportion of vaccine-preventable deaths.

1. Cover your nose and mouth with your sleeve or a tissue when you cough or sneeze--throw the tissue away after you use it.

2. Wash your hands often with soap and water, especially after you cough or sneeze. If you are not near water, use an alcohol-based hand cleaner.

3. Stay away as much as you can from people who are sick.

4. If you get Influenza, stay home from work or school. If you are sick, don't go near other people to avoid infecting them.

5. Try not to touch your eyes, nose, or mouth. Germs often spread this way.

1. Influenza viruses mutate frequently, making it very difficult to provide one influenza vaccination that will protect an individual for life.

2. Each year's Influenza vaccine is made up of three strains of the virus, based on an educated guess of which viruses will be most active during the upcoming influenza season. Occasionally, this projection may be wrong, and that year's vaccine will be less effective.

3. Influenza vaccine is not completely effective at preventing infection, especially with older individuals (although it does protect them from serious complications and death).

4. No attempt is made to vaccinate the entire population. Instead, Influenza vaccine is mainly recommended for certain groups such as people over 50, healthcare workers, people with chronic underlying illnesses, and others. Most recently the vaccine was recommended for use in infants and children age 6-59 months.

Measles

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Meningococcal

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Other factors make it more likely an individual will develop meningococcal disease, including having a previous viral infection, living in a crowded household, having an underlying chronic illness, and being exposed to cigarette smoke (either directly or second-hand).

Studies have also shown that college freshmen who live in dormitories are at an increased risk of meningococcal disease compared with others their age.

In addition to the antibiotic treatment, vaccination may be recommended for people two years of age and older if the person's infection is caused by meningococcus type A, C, Y, or W-135, all of which are contained in the meningococcal vaccine.

Mumps

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

The most well-known sign of mumps is "parotitis," the swelling of the salivary glands, or parotid glands, below the ear. Parotitis occurs only in 30%-40% of individuals infected with mumps.

Up to 20% of persons with mumps have no symptoms of disease, and another 40%-50% have only nonspecific or respiratory symptoms.

Pertussis

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Catarrhal stage: can last 1-2 weeks and includes a runny nose, sneezing, low-grade fever, and a mild cough (all similar symptoms to the common cold).

Paroxysmal stage: usually lasts 4-6 weeks, but can persist for up to 10 weeks. The characteristic symptom is a burst, or paroxysm, of numerous, rapid coughs. At the end of the paroxysm the patient suffers from a long inhaling effort that is characterized by a high-pitched whoop (hence the name, "whooping cough"). Infants and young children often appear very ill and distressed, and may turn blue and vomit.

Convalescent stage: usually lasts 2-6 weeks, but may last for months. Although the cough usually disappears after 2-3 weeks, paroxysms may recur whenever the patient suffers any subsequent respiratory infection. The disease is usually milder in adolescents and adults, consisting of a persistent cough similar to that found in other upper respiratory infections. However, these individuals are still able to transmit the disease to others, including unimmunized or incompletely immunized infants.

Although adults are less likely than infants to become seriously ill with pertussis, most make repeated visits for medical care and miss work, especially when pertussis is not initially considered as a reason for their long-term cough. In addition, adults with pertussis infection have been shown to be an important source of infection to infants with whom they have close contact.

Infants are also more likely to suffer from such neurologic complications as seizures and encephalopathy, probably due to the reduction of oxygen supply to the brain.

All close contacts younger than seven years of age should complete their DTaP vaccine series if they have not already done so. If they have completed their primary four dose series, but have not had a dose within the last three years, they should be given a booster dose.

Patients also need supportive therapy such as bed rest, fluids, and control of fever.

If someone has a recent culture-documented case of pertussis, he or she may not need immediate immunization against pertussis; however, a vaccine containing pertussis antigen will not be harmful, and they should continue on the routine immunization schedule for future protection against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis. If culture is lacking, even with a history of pertussis, do NOT withhold a dose of pertussis vaccine, if it is recommended per the routine schedule.

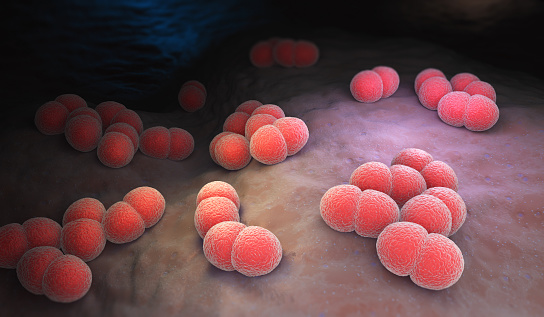

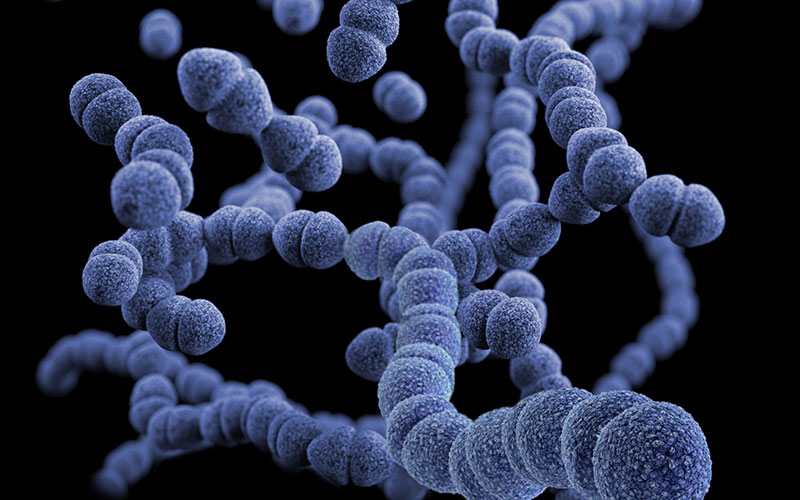

Pneumococcal

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Pneumococcal pneumonia (lung disease) is the most common disease caused by pneumococcal bacteria. The incubation period is short (1-3 days). Symptoms include abrupt onset of fever, shaking chills or rigors, chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, rapid breathing and heart rate, and weakness. The fatality rate is 5%-7% and may be much higher in the elderly.

Pneumococcal bacteremia (blood infection) occurs in about 25%-30% of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia. Bacteremia is the most common clinical presentation among children younger than age two years, accounting for 70% of invasive disease in this group.

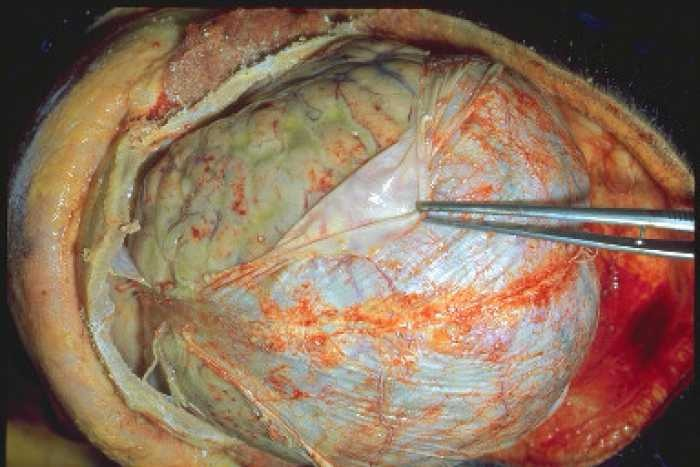

Pneumococcal meningitis symptoms may include headache, tiredness, vomiting, irritability, fever, seizures, and coma. Children younger than age one year have the highest rate of pneumococcal meningitis.

Pneumococci are also a common cause of acute otitis media (middle ear infection). Middle ear infections are the most frequent reason for pediatric clinic visits in India.

Case-fatality rates are highest for meningitis and bacteremia, and the highest mortality occurs among the elderly and patients who have underlying medical conditions. Despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy and intensive medical care, the overall case-fatality rate for pneumococcal bacteremia is about 20% among adults. Among elderly patients, this rate may be as high as 60%.

Before a vaccine was available in India, pneumococcal disease caused serious disease in children younger than age five years. Children younger than age two years are at the highest risk for serious pneumococcal disease.

Both pneumococcal vaccines are made from inactivated (killed) bacteria. The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) includes purified capsular polysaccharides from the bacteria that are “conjugated” (or joined) to a protein (a harmless variety of diphtheria toxin). The resultant conjugate vaccine is able to produce an immune response in infants and antibody booster response to multiple doses of vaccine.

The pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) contains long chains of polysaccharide (sugar) molecules that make up the surface capsule of the bacteria. Generally speaking, pure polysaccharide vaccines do not work well in children younger than 2 years, induce only short-term immunity, and multiple doses do not provide a “boost” to immunity.

Immunocompromising conditions include chronic renal failure, nephrotic syndrome, congenital or acquired immunodeficiency, iatrogenic immunosuppression, generalized malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus, Hodgkin disease, leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, solid organ transplants, congenital or acquired asplenia, sickle cell disease, or other hemoglobinopathies.

PCV13 can be given to adults age 65 years and older without these high-risk conditions based on shared clinical decision-making.

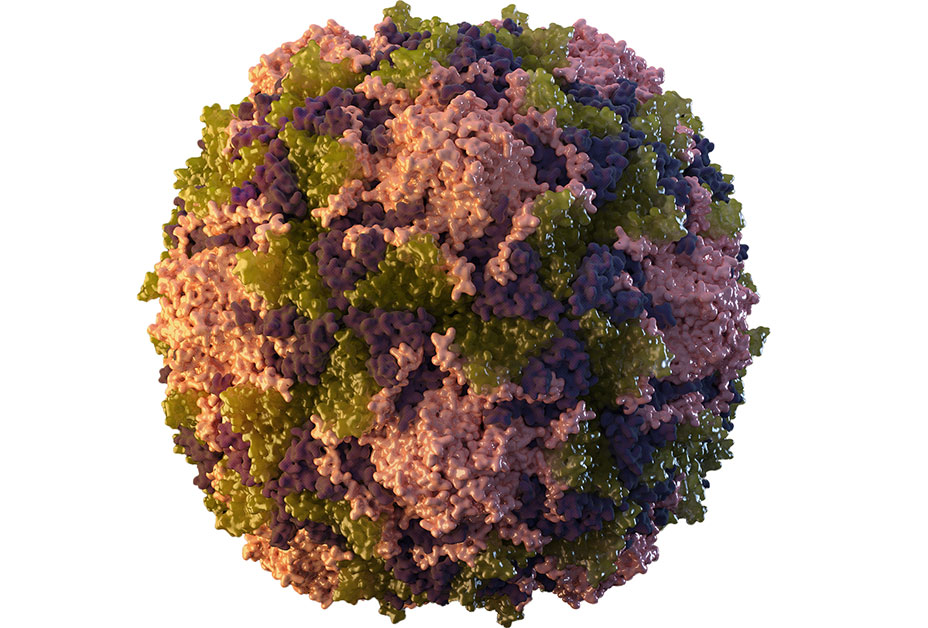

Polio

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Another 4%-8% of infected individuals have symptoms of a minor, non-specific nature, such as sore throat and fever, nausea, vomiting, and other common symptoms of any viral illness.

About 1%-2% of infected individuals develop nonparalytic aseptic (viral) meningitis, with temporary stiffness of the neck, back, and/or legs. Less than 1% of all polio infections result in the classic "flaccid paralysis," where the patient is left with permanent weakness or paralysis of legs, arms, or both.

• OPV is given as an oral liquid.

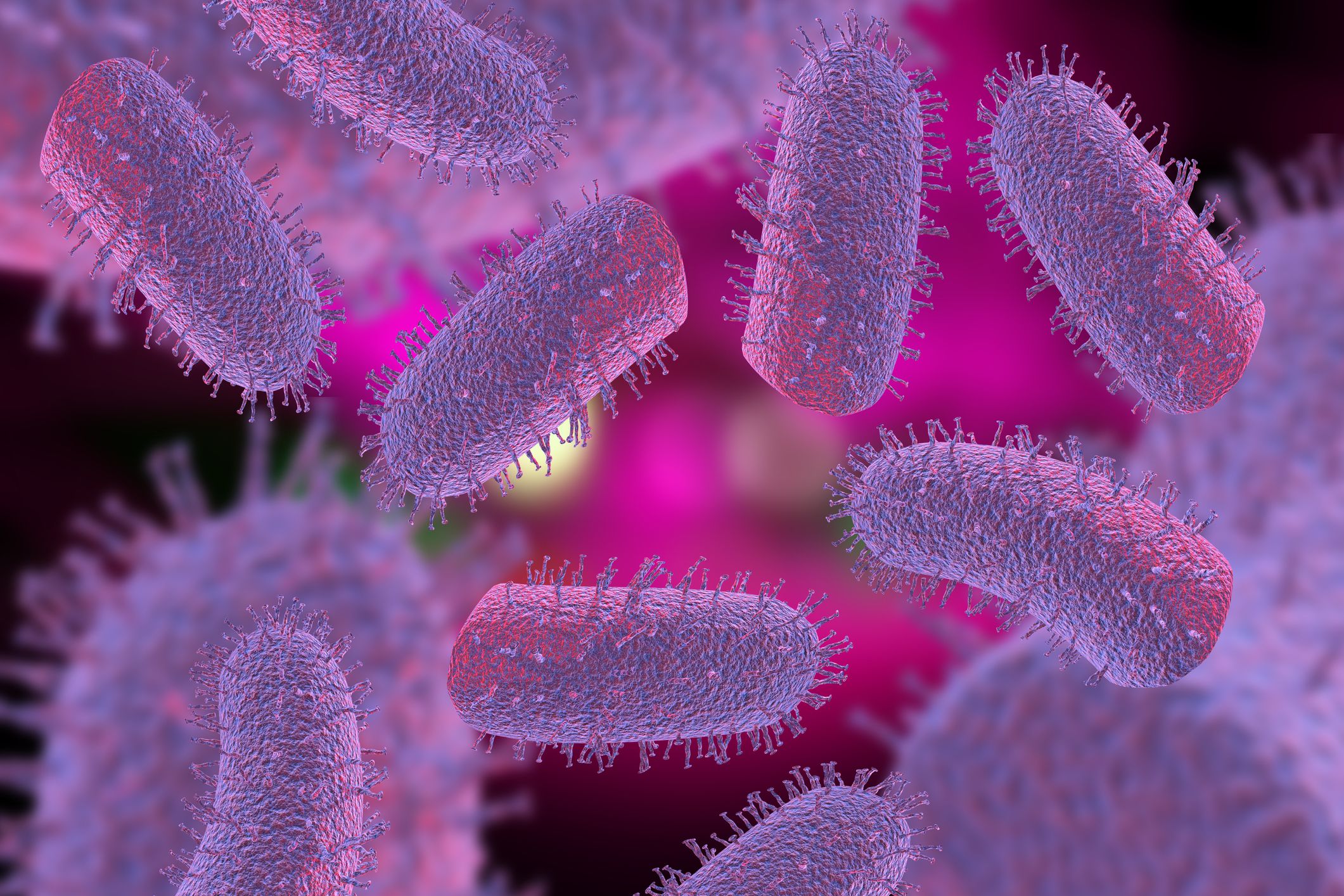

Rabies

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

You cannot get rabies from the blood, urine, or feces of a rabid animal, or from just touching or petting an animal.

Once symptoms appear, the disease is almost always fatal. Therefore, any person who has been bitten, scratched, or somehow exposed to the saliva of a potentially rabid animal should see a physician as soon as possible for postexposure treatment.

1. Clean the area immediately with soap and water for at least five minutes.

2. Immediately take a Tetanus Toxoid Vaccine short.

3. See a doctor/physician as soon as possible, ideally within 24-48 hours

Rabies is a big problem in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. Each year rabies kills more than 50,000 people and millions of animals worldwide.

Exposure to rabid dogs is the cause of over 90% of human rabies cases and over 99% of human deaths from rabies worldwide. Although vaccination of dogs and elimination of strays has been shown to effectively prevent most cases of human rabies, the cost of such a control program is beyond the reach of most developing countries.

2. Contact animal control to remove stray animals or animals acting sick or strange in your neighborhood.

3. Never touch or approach unfamiliar animals, domestic or wild. Don't touch dead animals. Teach your children the same.

4. Seal openings into your home to prevent wild animals from gaining entrance.

5. If you do get bitten by an animal, wash the wound with soap and water for at least five minutes and then seek medical care.

Rotavirus

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Rotavirus is very stable and may remain viable in the environment for months if not disinfected.

Rubella

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

The most serious complication of rubella infection is Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS), the result when the rubella virus attacks a developing fetus. Up to 85% of infants infected during the first trimester of pregnancy will be born with some type of birth defect, including deafness, eye defects, heart defects, mental retardation, and more. Infection early in the pregnancy (less than 12 weeks gestation) is the most dangerous; defects are rare when infection occurs after 20 weeks gestation.

Tetanus

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Varicella (Chickenpox)

F.A.Q About the Disease and Vaccines

Although some vaccinated children (about 2%) will still get chickenpox, they generally will have a much milder form of the disease, with fewer blisters (typi¬cally fewer than 50), lower fever, and a more rapid recovery.

The vaccine almost always prevents against severe disease. Getting chickenpox vaccine is much safer than getting chickenpox disease.